Rony Griffit | 2021

Directing a Stream of Consciousness

Interview with artist Joshua Griffit

by Rony Griffit

“I take an image from someone or something, an image that comes from the need to create a new form or develop it, an image whose raw form is within me, and only in a format that summons the image can I reach it and bring into being a new form that was not there before.” Zvi Tolkovsky

What was your first encounter with the art world?

In elementary school we were shown a film once a week. The person screening the film would come with two projection machines, one for the film and one for the translation. The translation revolved to the left of the screen, but because the projectionist was not a master of languages, there were sometimes quite amusing results in which the translation did not match what we saw on the screen. Dialogues between a guy and a girl or marriage proposals were sometimes accompanied by war scenes. Occasionally there were scenes he didn’t want us to see, and in those cases, he would cover the projector with his hand and shout, “Be quiet or I’ll stop the screening!”. This is how I first witnessed censorship in action.

Another early memory is when I went to Haifa for a family visit as a twelve-year-old boy. In the building next door, there was a basement where two painters were working – I think there were Russians, a father and a son. They had piles of small paintings of vases with flowers. The father painted the vases and the son the flowers or vice versa, like a simple but sophisticated production line – with no hesitations, without fixing anything, no worrying about the quality of the work; they just worked like workers who had to get something done, and I was fascinated by the process. I knew that in painting and art you used paint, a canvas and a brush, but they were not dealing with art, but rather production.

In retrospect, I think this is how it should work – let the stream of consciousness flood you and pass through your hand to the paper or canvas and only afterwards look, erase, add, take away, conceal some parts. That encounter had an impact on me. The first stage of creating a piece of art, in my opinion, should be “art without boundaries,” without barriers or filters, just create with the knowledge that what you do at first, the "prima vista", is not the end result.

What was your first encounter with drawing on paper?

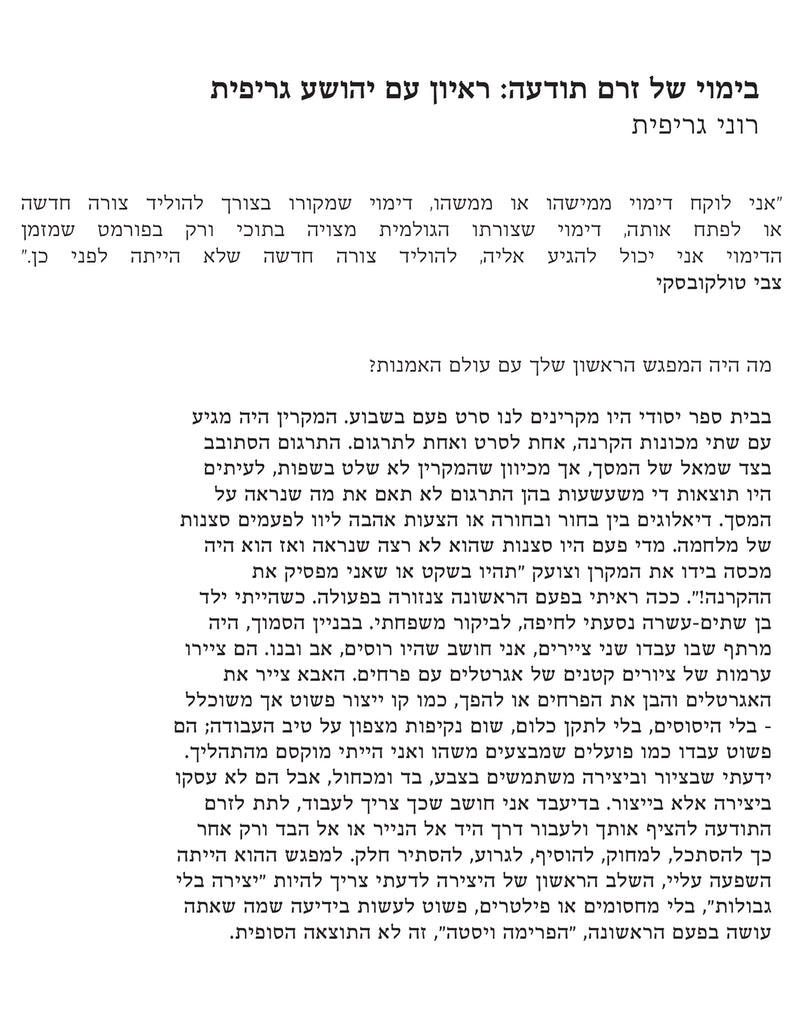

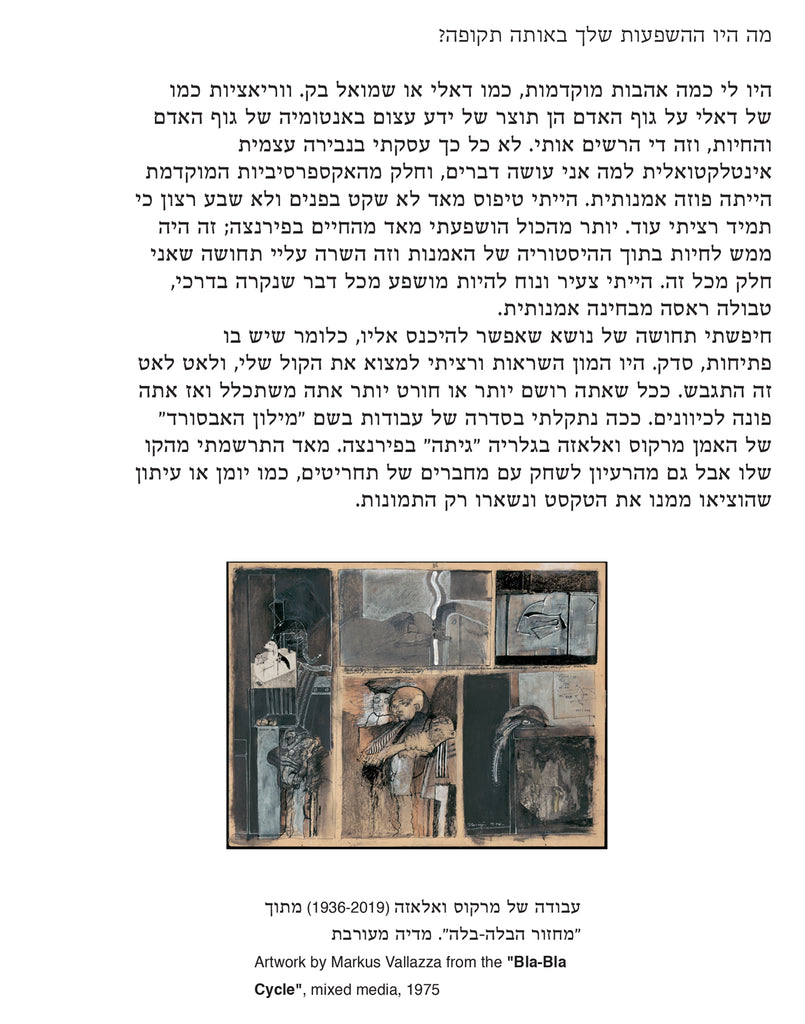

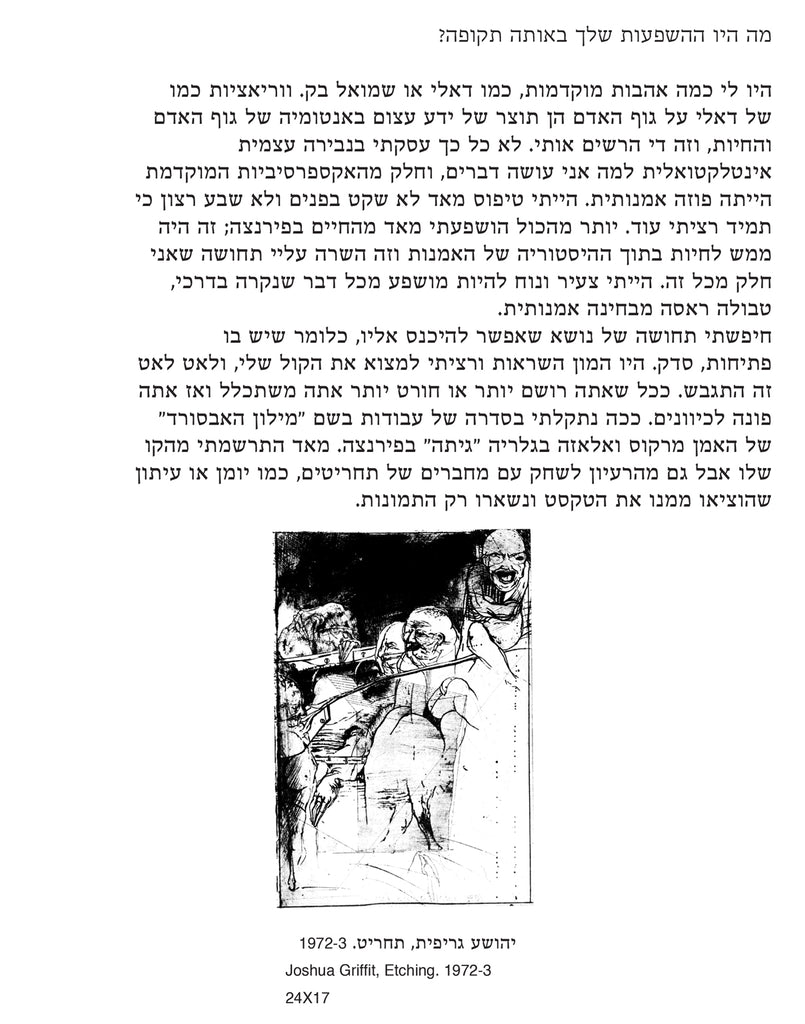

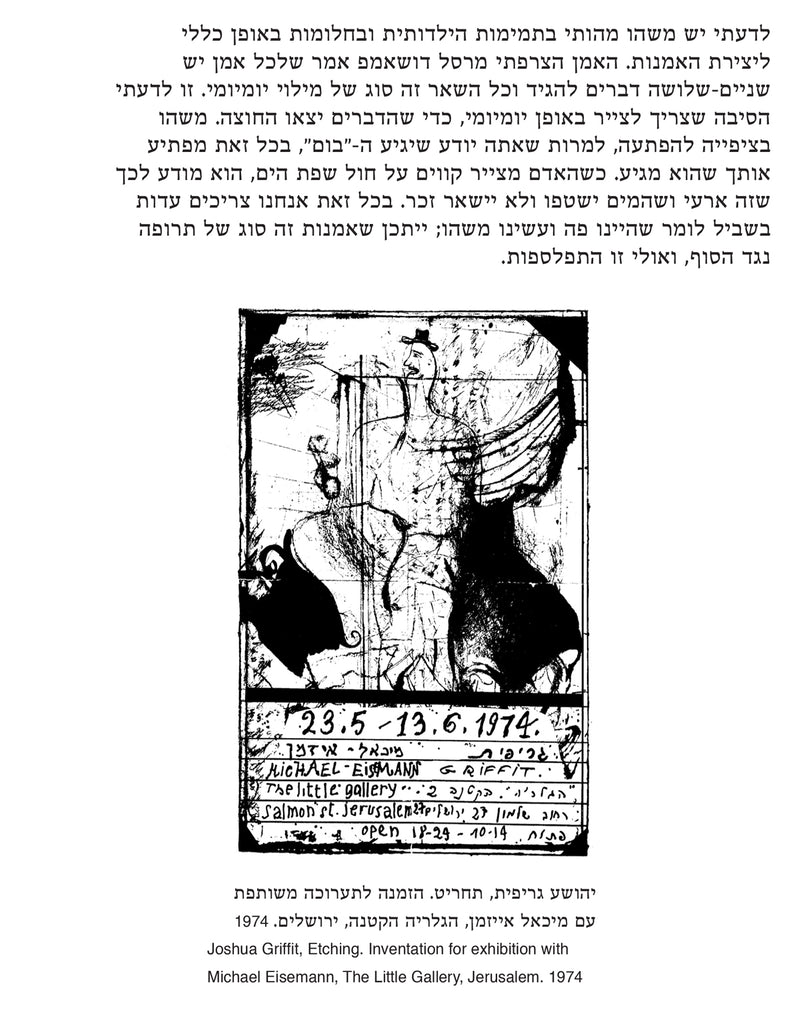

A year or two after that visit to Haifa, I started making charcoal drawings of distorted faces. I usually take an existing form from someone who has defined well the image that I had in mind, and then I decide how to change it and make it my own. However, those drawings just came to me naturally. At the age of fifteen, I started going to Moshe Rosenthalis in Jaffa, where every week we would draw a different still life, like a vase or geometric shapes. At the age of seventeen, I went to Bezalel, where I took a drawing course, and from there I continued to Italy, where I studied anatomy. At the Fine Arts Academy in Florence, there was a nude model every day for two hours, and that's basically the only thing I did. Most of the etchings that I presented at my first exhibition I had already done in Israel. I think the difference between the etchings and my early drawings is simply due to the fact that I had not yet mastered the secrets of drawing and therefore could not “go wild”.

Who were your influences at that time?

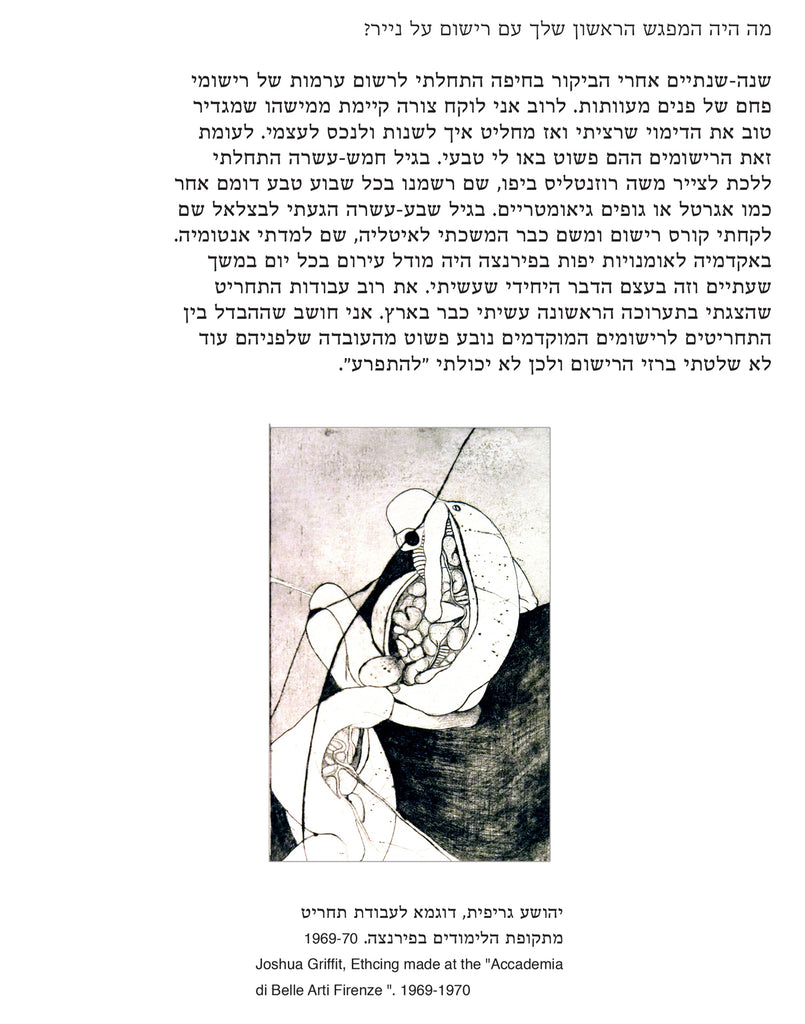

I had some early loves, like Dali and Samuel Bak. Variations like Dali's on the human body are the product of a vast knowledge of anatomy, and it quite impressed me. I wasn’t really concerned with intellectual introspection as to why I do the things I do, and part of my early expressiveness was an artistic affectation. I was a very restless type, and never satisfied because I always wanted more from myself. More than anything, I was greatly influenced by life in Florence; it was really living within the history of art, and it made me feel like I was a part of it all. I was young and comfortable being influenced by everything that happened to me, an artistic “tabula rasa”. I was looking for the feeling of a subject that I could really get inside of, meaning that there was openness, a crack. There was a lot of inspiration and I wanted to find my voice, and slowly it took shape. The more you draw or etch, the better you get, and then you take on new directions. That's how I came across an exhibition and saw a series of works called “Absurdes Vokabularium” by the artist Markus Vallazza at Galleria Goethe in Florence. I was very impressed by his fine line but also by the idea of playing with compositions of etchings, like a journal or a newspaper from which the text was taken out and only the pictures remained.

Tell me about creating the etchings you did in Florence.

In an eleven-meter shot in football, if the kick is strong and accurate, the goalkeeper has no chance of stopping the ball due to the size of the goal, so he bets on a corner and jumps towards it as soon as the ball is kicked. That's how I did the etchings. I just had the intention to make it interesting to the viewer, a kind of drama – to leap into a corner. Even then I knew that there is no risk in art, and that in the worst-case scenario, the piece wouldn’t turn out well. I set myself the goal of making an etching every day and acting mainly out of intuition. The work was done before I could start explaining and justifying it to myself, and I welcomed any line or form that surprised me. I figured that if I was able to surprise myself as the first viewer of the piece, it might be intriguing and interesting to other viewers. The thinking came in retrospect, and I don’t regret that; if I had a specific ideology that the pieces served, or were examples of, I would feel like a walking placard or a politician.

In my opinion, childlike innocence and dreams in general are essential for creating art. The French artist Marcel Duchamp said that every artist has two or three things to say, and the rest is a kind of filler. This, I believe, is the reason you have to paint on a daily basis, for things to emerge. There’s something about anticipating a surprise – even though you know the “boom” is coming, it still surprises you when it comes. When a person draws lines in the sand on the beach, he is aware that it is temporary and that the water will wash them away, leaving no trace of them behind. Even so, we need a testimony to the fact that we were here and that we did something; art may be a kind of cure for death, or maybe I’m just philosophizing.

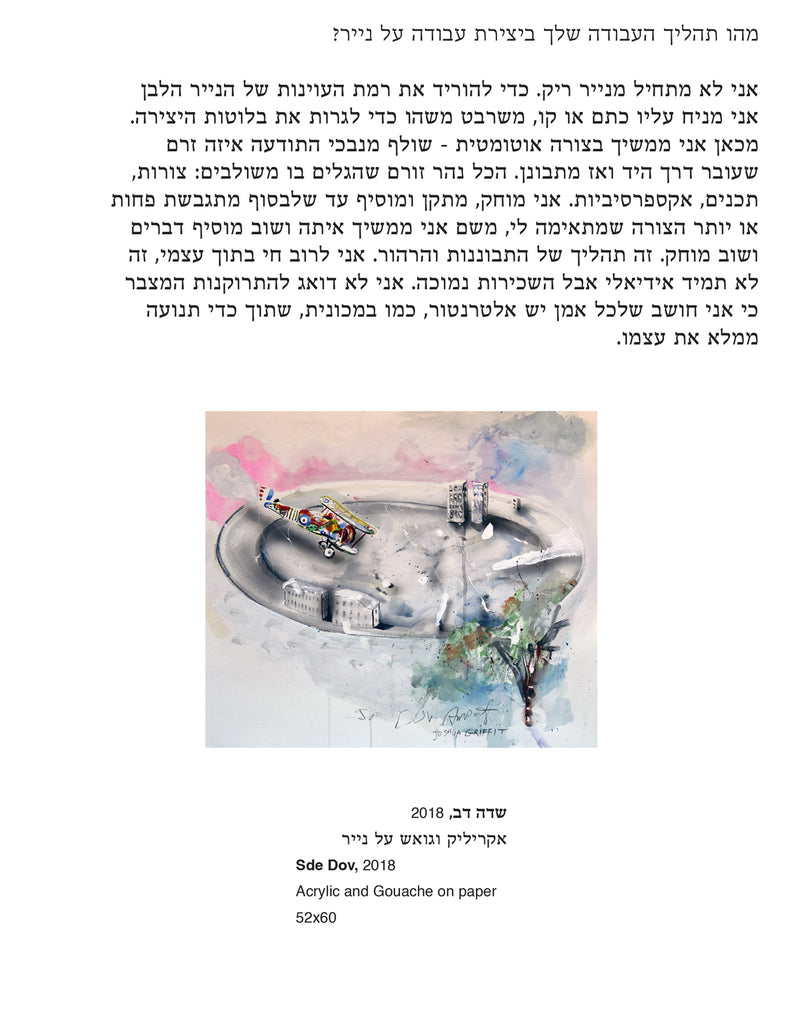

How do you make a work on paper?

I do not start from a blank page. To decrease the level of intimidation of the blank paper I place a patch of color or a line on it, sketching something to stimulate the piece. From there I continue automatically – pulling from the depths of my consciousness a current that passes through my hand, and then I look. Everything is a flowing river in which the waves are intertwined; forms, content, expressiveness. I erase, correct, and add until finally the composition I am happy with is more or less formed; from there I continue and once again add and remove things. It’s a process of observation and contemplation. I mostly live within myself; it’s not always ideal but the rent is cheap. I don’t worry about my battery draining because I think every artist has an alternator, like in a car, that charges itself while it’s in motion. The paper responds quickly, so it's a simple dialogue, sometimes seeming to tolerate everything.

Since smart phones, I find there are many more potential images surrounding me. The transition from a slide projector to a projector that’s directly connected to a computer has also made things easier and more accessible. It’s quite automatic for me – sometimes I take quotes from others in their external form, both because it’s beautiful to me but also because it’s an index of quality. Being an agent of quality is like quoting a good line from a song. To sum up, I can say that I would like to leave a mark of quality behind. Although I don’t have a definition of quality, I am able to identify it. This is true for etchings, paintings and works on paper.

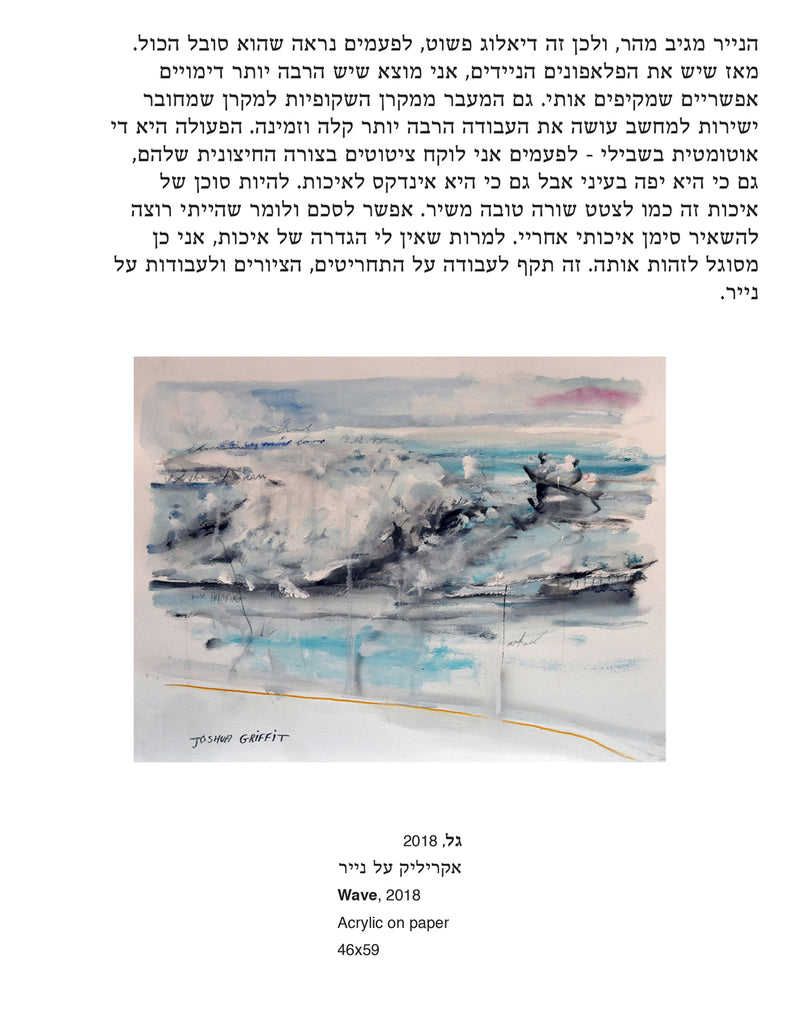

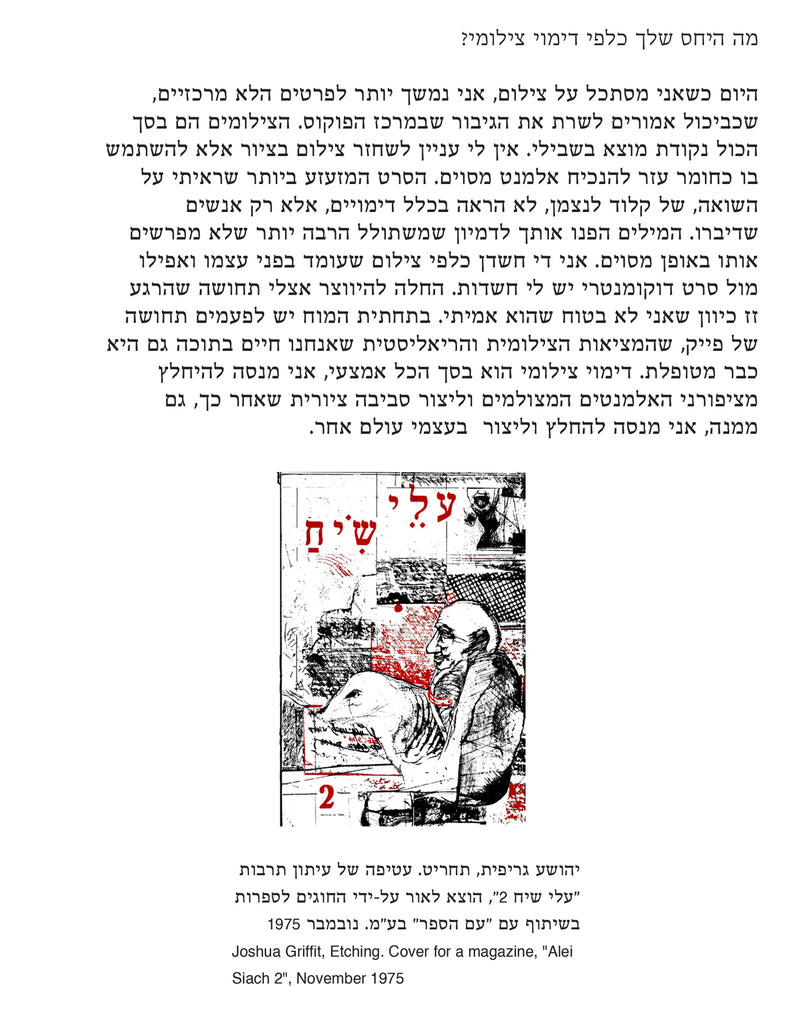

What is your approach towards the photographic image?

Today, when I look at photography, I am more drawn to the non-central details, which are purportedly intended to serve the main focal point. Photography is just a starting point for me. I have no interest in recreating a photograph in a painting, but rather in using it as a supplementary material to present a particular element. The most shocking film I have seen about the Holocaust, by Claude Lanzmann, showed no images at all, only people talking. The words lead you to imagine much more wildly than if it were interpreted in a certain way. I tend to be quite suspicious of photography that stands on its own, and I’m suspicious even of documentary films.

I start to get the feeling that the moment is moving because I'm not sure it's real. Somewhere deep down in the brain there is sometimes a sense of “fake,” that the photographic and realist reality we live in has already been treated. A photographic image is merely a means for me to create pictorial imagism for myself. I try to escape from the clutches of the photographed elements and create a pictorial environment that I later also try to extract myself from and create another world for myself.

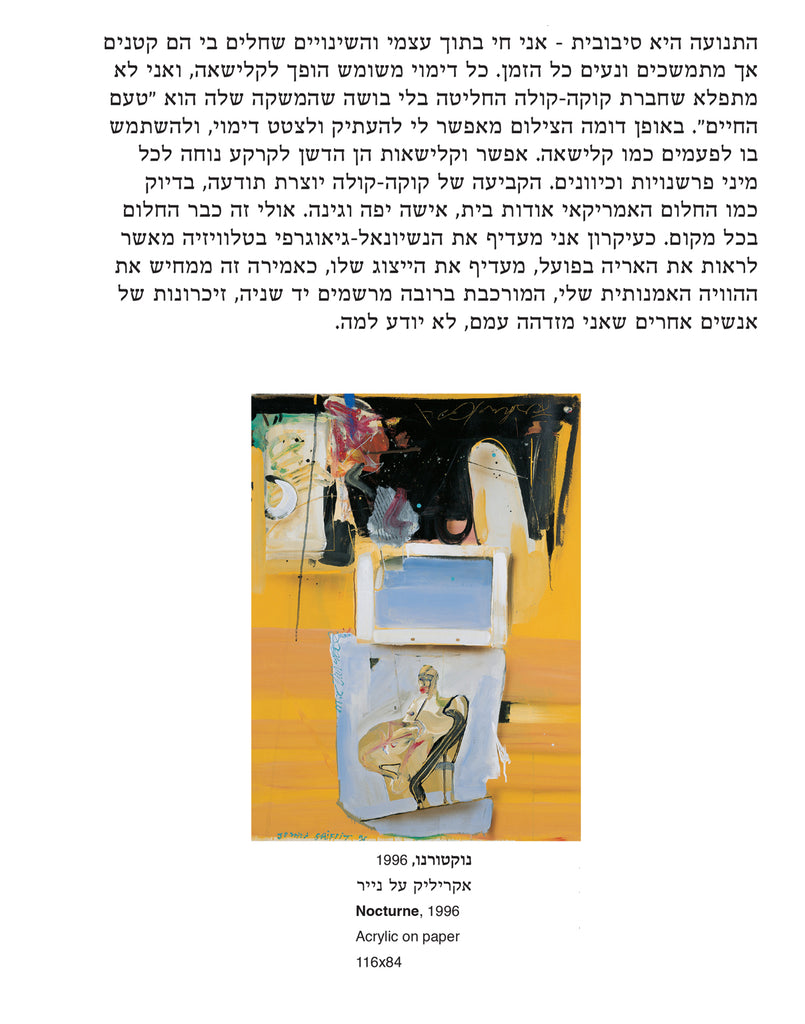

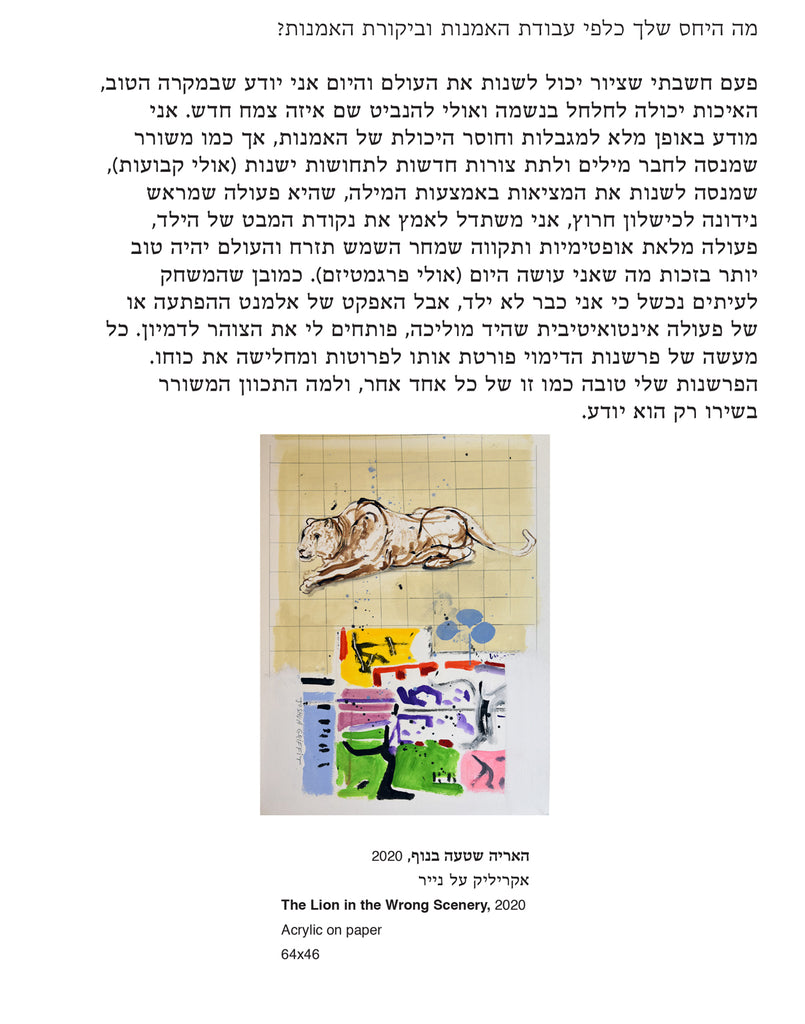

The movement is circular; I live within myself and the changes that take place in me are small but continuous and happening all the time. Every used image becomes a cliché, and I'm not surprised that the Coca-Cola company shamelessly decided that its drink was ״the taste of life.” Similarly, photography allows me to copy and quote an image, and sometimes use it as a cliché. Clichés can be a fertilizer for soil that is suitable for all sorts of interpretations and directions. Coca-Cola's proclamation creates consciousness, just like the American dream of a home, a garden, and a beautiful wife. Maybe that’s now the dream everywhere. In principle, I prefer to watch National Geographic on TV rather than seeing the actual lion; I prefer its representation. This statement illustrates my artistic experience, which consists mostly of second-hand impressions, memories of other people I identify with and don’t know why.

What is your view on art and criticism?

I once thought that a painting could change the world, and today I know that at best, quality can seep into the soul and maybe plant some new seed there. I am fully aware of the limitations of art and the things it cannot do, but like a poet trying to write words and give new forms to old (perhaps eternal) feelings, trying to change reality through the written word, which is doomed to fail, I try to adopt a child's perspective: The creating itself as an act full of optimism and hope that tomorrow the sun will shine and the world will be a better place thanks to what you are doing today (perhaps pragmatism). Of course, this game sometimes fails because I am no longer a child, but the element of surprise or intuitive action led by the hand opens the window to my imagination. Every attempt to interpret an image breaks it down and reduces its power.

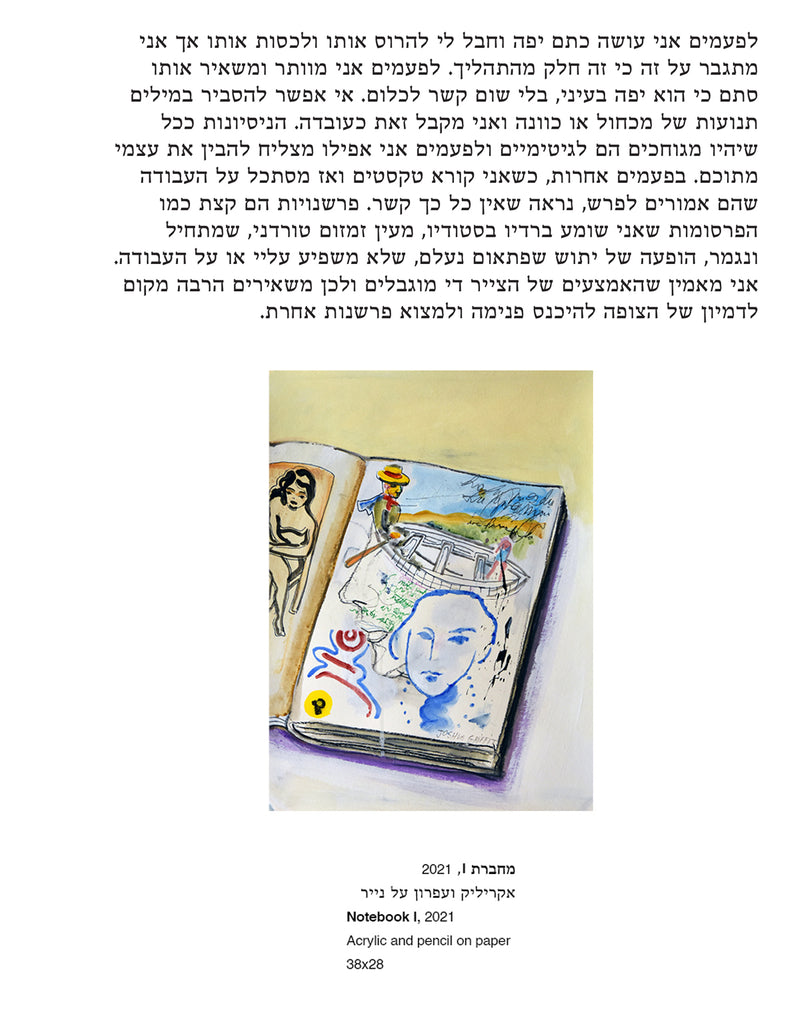

My interpretation is as good as anyone else’s, and what a poet meant in his or her poem only he or she knows. Sometimes I make a nice patch of color, and it seems a shame to ruin it and cover it up, but I get over it because it's part of the process. Sometimes I give up and leave it just because it’s beautiful to me, though it has nothing to do with anything else. It’s impossible to explain in words the movements of a brush or an intention, and I accept this as a fact. The experiments, as ridiculous as they may be, are legitimate, and sometimes they even help me understand myself. Other times, when I read texts and then look at the work they are supposed to interpret, there seems to be little connection. Interpretations are a bit like the commercials I hear on the radio in the studio, a kind of annoying buzz, that starts and ends, like a mosquito that appears and then suddenly disappears, that doesn’t affect me or my work. I believe the painter's tools are quite limited, and therefore a lot of room should be left for the viewer's imagination to dive inside and find another interpretation.

What do you do differently in your works on paper?

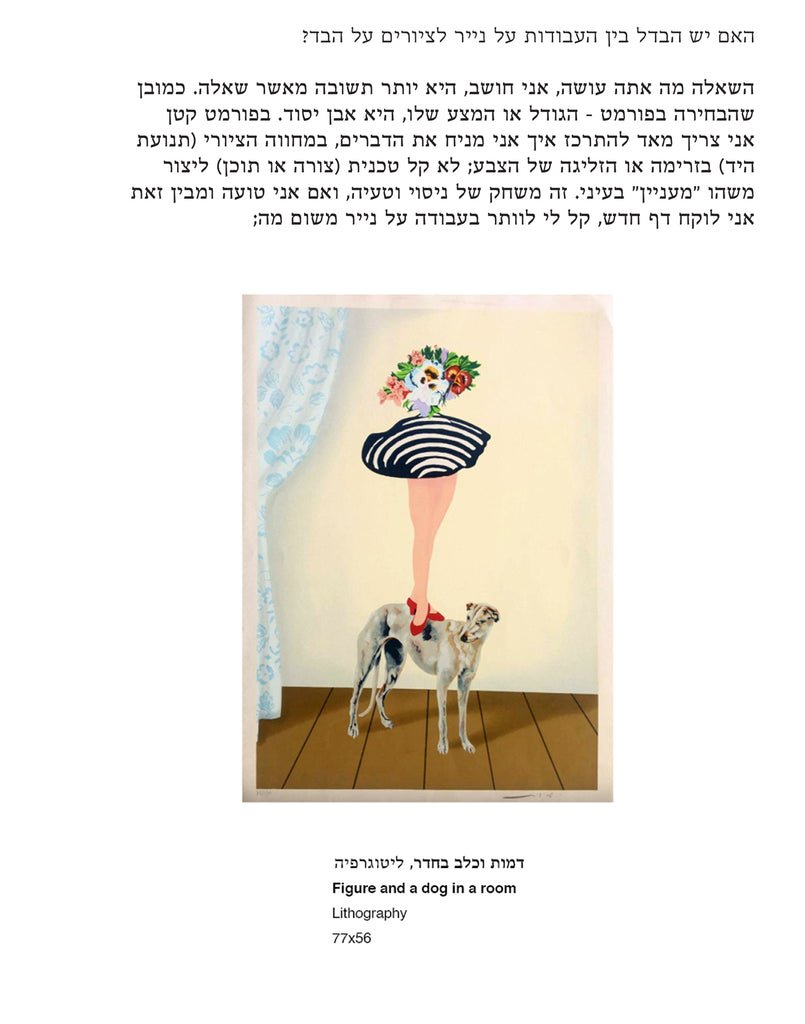

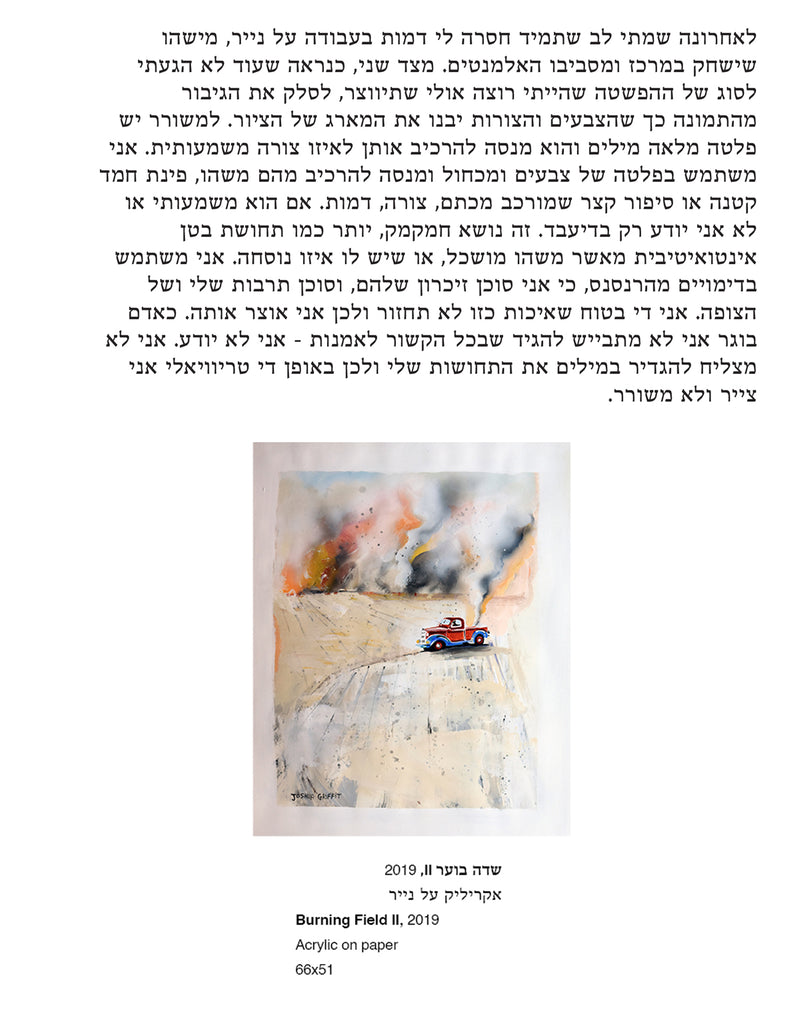

I find plastic artists trying to explain what they are doing sightly ridiculous. The question of what you do, I think, is more of an answer than a question. Of course, the choice of format – its size or base, is a cornerstone. For a small format I have to concentrate very hard on how I place things, on the gesture (hand movement) in the flow or dripping of the color; it is not technically easy (form- or content-wise) to create something that I find “interesting.”

It's a game of trial and error, and if I'm wrong I take out a new page. Recently I noticed that I’m always missing a character on a work on paper, someone to be in the center and surrounded by other elements. On the other hand, I probably haven’t yet reached the kind of abstraction I would like to create, removing the central figure from the image so that the colors and shapes produce the fabric of the painting.

The poet has a full palette of words, and he tries to put them together in some meaningful way. I use a palette of paints and a brush and try to make something out of them, a charming place or a short story that consists of a patch of paint, a shape, a figure. Whether it is significant or not I only know in retrospect. It's an elusive subject, more like an intuitive gut feeling than something intelligent or having some formula. I use images from the Renaissance because I am their agent of memory, and an agent of culture for myself and the viewer. I'm pretty sure such quality will not return, so I safeguard it. As an adult, I am not ashamed to say that when it comes to art, I don’t know. I cannot put my feelings into words, so, rather trivially, I am a painter and not a poet.